Co-op Forum Highlights Economic Divide and the Fight for City Council

- Ronaldo Rodriguez Jr.

- Aug 20

- 9 min read

Updated: Aug 22

On July 31, 2025, Cleveland Owns' Co-Op Circles hosted an Economic Policy Candidate Forum at Pilgrim Congregational United Church of Christ on W. 14th Street. The event drew residents from across the city eager to hear directly from City Council candidates ahead of the September 9th primary election.

Community members pressed candidates on issues of transparency, accountability, and neighborhood investment, pushing them to go beyond talking points and explain how their policies would deliver real change.

Unlike a debate, the forum created a safe space for reflection and direct engagement. For many in the audience, it was a rare opportunity to compare candidates side by side on the issues shaping daily life in Cleveland. With the primary election just weeks away, the evening highlighted both the urgency of the city’s economic challenges and the possibility for new leadership to chart a different course.

Cleveland Co-Op Circles, a grassroots network focused on economic justice and working towards building a local cooperative economy, opened the evening with a welcome song and land acknowledgment, grounding the forum in a spirit of community and collective responsibility.

Food was shared by Little Africa Food Cooperative and candidates mingled with community members before taking their seats for the evening’s questions.

The event was moderated by Trevelle Harp of the Neighborhood Leadership Institute, who framed the forum around Cleveland’s shifting political landscape. After the 2020 Census triggered a charter-mandated redistricting, City Council shrank from 17 seats to 15. This year, 43 candidates are competing for those seats, making it one of the most wide-open elections in recent memory.

He reminded residents that every City Council seat — and the mayor’s office — will be on the ballot this year, underscoring the weight of the decisions ahead. "The entire city government is on the ballot," said Harp.

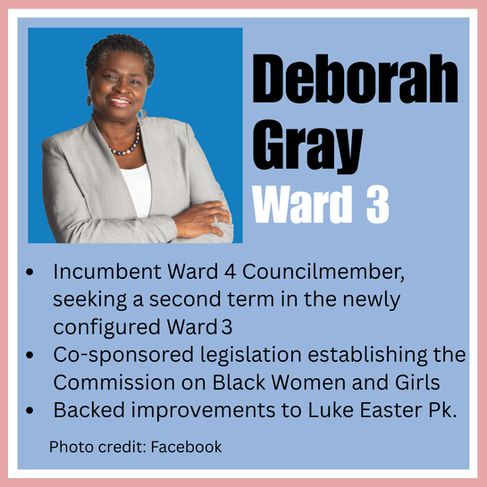

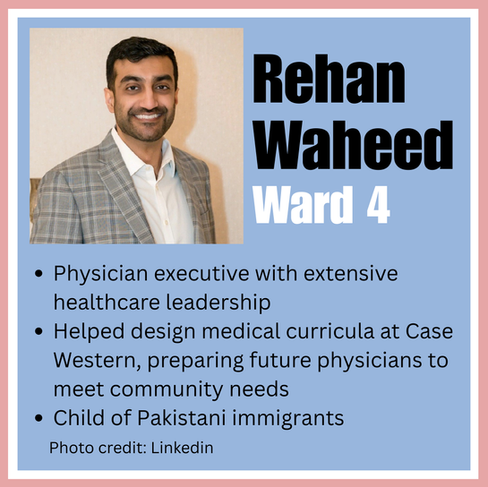

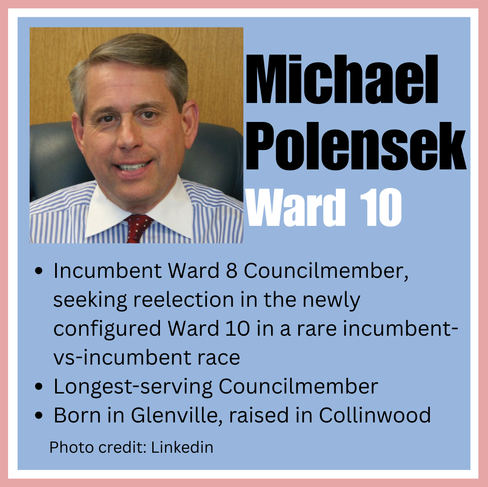

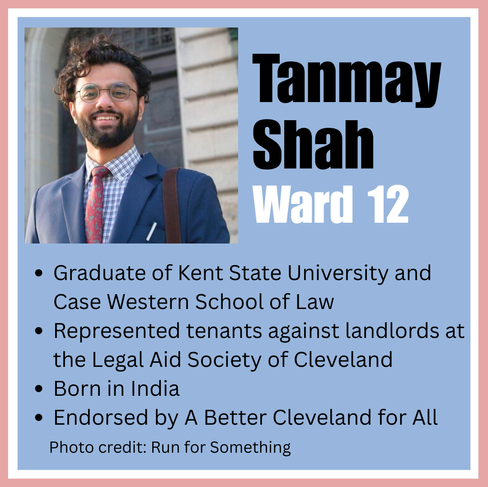

With 13 candidates in attendance, the forum was divided into two parts, with LaShorn K. Caldwell (Ward 3), Lesa Jones Dollar (Ward 1), Deborah M. Gray (Ward 3), Michael D. Polensek (Ward 10), Tanmay Shah (Ward 12), and Rehan Waheed (Ward 4) up first. Each candidate introduced themselves with one-minute opening remarks.

A City Divided by Investment

Over the course of the forum, a theme emerged: the contrast between a downtown flush with development and neighborhoods that feel increasingly abandoned by City Hall.

LaShorn Caldwell reminded the audience that neighborhood neglect isn’t new, pointing back to promises made under former Mayor Frank Jackson.

"We’re not covering the basics," she said. "When Mayor Jackson was in office, he told us: please let the city get Downtown and the Near West Side together, and I promise you, we’re coming to the Southeast Side."

Caldwell noted that years later, many residents on the Southeast Side are still waiting for those investments to arrive.

Waheed argued that Cleveland always manages to find money for downtown projects while neighborhoods are told to make do with less.

"We need to stop exploiting our own city and our own resources from our own people,” he said. “When we talk about funding, we can always find a billion dollars in subsidies for downtown or a big project. When it comes to our neighborhoods, suddenly it’s a budget issue. 'I’ve got a budgetary problem.' Well, where is all the other money coming from?"

He described what that neglect looks like. "I see it with my own eyes. I’ve seen what’s been built downtown, and I’ve seen neighborhoods continue to worsen. You look around and see roads left crumbling, waterline breaks that go weeks without repair, tree lawns neglected, and power outages with every storm. The priority hasn’t been us. We deserve better. We need a city that puts people first."

Several other candidates criticized the City’s continued use of tax subsidies for large developers like Bedrock and the Haslam Sports Group, arguing that those funds could be better used to repair streets, fund affordable housing, and improve basic services.

"Capitalism is eroding our neighborhoods," said Shah. "I’m running because our city doesn’t work for the working class. Right now it works really well for the rich and the ultra-wealthy, and it is time that it started working for the working class."

Money, Power, and Transparency

When asked how they would involve residents in decisions about public funding, incumbents and challengers offered sharply contrasting views.

Councilmember Gray pointed to her efforts to gather feedback through surveys and monthly meetings. "We put together a list of what residents wanted to see," she said. "Over the past few years, we’ve been building back the ward, and residents get monthly updates showing how the money was spent."

Veteran Councilmember Polensek reminded the audience of the limits to Council’s authority. "Council does not hire, we do not fire, we do not deploy, we do not administer. That’s the law in the City of Cleveland. We can propose any kind of program we want, but it is another thing to fund it. It’s another thing to make sure it works."

Rehan Waheed warned that Cleveland has been relying on one-time federal dollars to cover neighborhood needs without a long-term strategy. "We haven’t really thought about our own future, because we’ve been giving it away [to developers]," he said.

Editor’s note: Cleveland received approximately $512 million in ARPA (American Rescue Plan Act) funds, one of the highest per-capita awards in the nation. These one-time dollars had to be obligated by the end of 2024 and must be spent by 2026. City leaders will soon face tough choices about how to sustain programs once the money runs out, amid uncertain federal support going forward.

The night’s most contentious moment came when candidates were asked about the Council Leadership Fund — a political action committee often used to shield incumbents. The question first went to Lesa Jones Dollar, who admitted she wasn’t familiar with it.

The room fell quiet. After a long, awkward silence, Tanmay Shah jumped in: "It’s a slush fund."

He went on to explain that the PAC, fueled by annual fundraisers and donations from the city’s wealthy, is controlled at the discretion of the council president, who primarily uses it to protect sitting members. "I’m sure Mike (Polensek) can explain further if he wants," Shah snidely added, drawing applause.

"I raise my own money," said Polensek.

Part Two

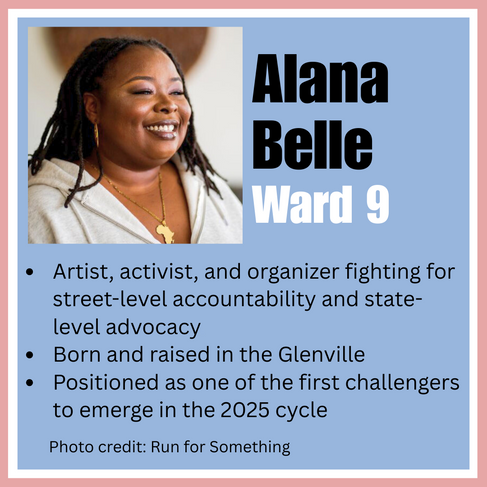

The second half of the forum featured candidates, Kris Harsh (Ward 4), Austin N. Davis (Ward 7), Mohammad Faraj (Ward 7), Teri Ying-Liang Wang (Ward 8), Leon Meredith (Ward 8), Alana Belle (Ward 9) and Nikki Hudson (Ward 11), as pictured below from left to right.

As with the first round, each offered a one-minute introduction, sharing their personal stories and motivations for running while echoing frustrations about disinvestment and outlining their own approaches to housing, economic development, and neighborhood priorities.

Harsh, the sole incumbent, emphasized his background as a community organizer with ACORN, citing his role in raising Ohio’s minimum wage, fighting foreclosures, and unionizing charter school teachers.

Davis drew on his professional experience inside City Hall, pledging to apply that knowledge at the neighborhood level, while Faraj pointed to his background in anti-money laundering and banking compliance, framing his campaign around accountability and reliable services.

Wang, a Tremont resident running in Ward 8 on Cleveland’s East Side, described rising rents and food insecurity as motivation for seeking office. Meredith, also running in Ward 8, presented himself as a "professional volunteer" for the past seven years.

Belle, an artist and activist from Glenville, cast herself as a community organizer seeking to represent Ward 9.

Hudson highlighted her grassroots record in Ward 11, from fighting nuisance liquor permits to protecting Cudell Park.

From there, the discussion quickly turned to the challenges of housing and the role of city government in ensuring basic services.

Housing Crisis

While the first half of the forum underscored concerns about downtown subsidies, the second half made clear that housing has become a defining crisis across Cleveland’s neighborhoods.

Wang drew a stark picture of the stakes, estimating that "probably half the ward is spending half their income on either rent or a mortgage." She argued that Cleveland’s low housing values discourage banks from issuing mortgages, leaving families trapped in unstable rental markets or cost-burdened.

Her solution was for the city itself to act as developer, lender, and landlord. "Local government needs to step in — provide for those loans, buy public housing, fix it up, and then you can either rent it out or sell it," she said.

Harsh urged realism, reinforcing Polensek’s point from the first half: "Let's remember that Cleveland City Council is a legislative body. Nothing gets done without a majority vote. If anybody tells you they're gonna go down there with a unilateral agenda and just get things done on their own, they're misleading you. There needs to be a majority for any idea that gets passed through council."

He pointed to his work securing $1 million for tenant support and championed modular housing as a way to quickly expand supply at lower cost.

Davis warned that Ward 7 faces some of the steepest housing pressures in the region, displacing both young families and longtime residents. "Kids that grew up here can’t afford to live here anymore. Folks who are aging in place are scared about the future," he said. "We’re not going to be able to get out of this until we start building more homes. Yes to market rate, yes to affordable, yes to public housing as well.”

Faraj highlighted how the housing crisis is squeezing Cleveland’s longtime residents, saying he’s heard from "countless seniors, many who have invested their entire lives here, who now can’t afford their property taxes — yet can’t afford to move anywhere else.”

Belle pointed to deteriorating housing in Ward 9, stressing the need to protect elders while also prioritizing mixed-income developments that allow residents of all ages and income levels to live in "well-maintained communities, regardless of how much they earn or can afford."

Hudson framed housing through the lens of health, calling lead poisoning one of the most urgent but overlooked threats facing Cleveland’s children. Meredith spoke, for his part, about abandoned homes as wasted opportunity, urging creative reuse of land and housing stock to stabilize communities.

He pointed to Cleveland’s East-West divide, saying Ward 8 lacked the kind of programs and investment seen elsewhere in the city. "On my side of town, the programming is not sufficient. A lot of things are beautiful on this side of town, but we have a lot of catching up to do."

Together, their remarks painted a sobering picture: whether in Glenville, Tremont, Old Brooklyn, or Hough, residents are struggling to stay in their homes — and candidates see housing policy as central to Cleveland’s future.

Building a More Democratic Economy

From housing, the conversation moved to broader questions of economic democracy, models where residents, workers, and tenants share ownership of businesses and housing.

Faraj pushed for stronger oversight of tax increment financing and tougher community benefits agreements. He pointed to a new playground in Duck Island not as a win but as an indictment. Families had to pool their own money to help get it built, he noted, when such amenities should be standard in agreements with developers.

Where Faraj emphasized holding developers accountable, Davis turned to the workplace. He cast unions as Cleveland’s most durable engine of economic democracy, highlighting his role in passing pay equity legislation inside City Hall to prevent employers from using salary history to perpetuate wage gaps. For Davis, organized labor remains the city’s best tool for lifting wages across the board.

Harsh, meanwhile, described himself as more conduit than architect, someone who listens for good ideas and fights to implement them. He cited his work on medical debt relief, where a modest allocation of ARPA funds wiped out more than $160 million in residents’ unpaid bills, as an example of how council can directly reduce financial burdens when it acts creatively.

Belle envisioned mutual aid and resource-sharing networks as the most immediate path to a fairer economy. "We’re not able to trust what is happening in the White House, we’re not able to trust what is happening in the State House, but we should be able to trust our neighbors," she said.

Different strategies, same goal: whether through tougher deals with developers, stronger unions, innovative debt relief, or neighborhood-based support networks, candidates argued that Cleveland’s future depends on shifting economic power back to its communities after decades of speculative investment and neglect.

Food and Schools

When asked about food security for children, Wang offered an ambitious proposal: municipally owned and operated grocery stores. She argued that the city should subsidize grocers, guaranteeing their profitability "so that they are incentivized to stay in those neighborhoods," and estimated that "it would probably take about a million dollars to build these grocery stores."

For Belle, hunger was both a moral and practical challenge: "If your neighbor is hungry, you are not safe." She rejected the term "food desert," arguing that deserts are natural phenomena, while Cleveland’s lack of access to fresh food is man-made. "What’s happening with food is not a natural thing," she said. "We are being denied, systemically."

Hudson emphasized community gardens and grassroots solutions, pointing to her own experience with neighborhood campaigns to reclaim public spaces.

Meredith approached food insecurity from a different angle, advocating for lifestyle changes and healthier eating. Harsh added that "the issue in Cleveland probably has more to do with bad diets than malnutrition," before shifting the conversation to the issue of mayoral control of Cleveland’s public schools, calling it his "greatest frustration."

Speaking both as an elected official and as a parent, he argued the current system leaves families voiceless. "The only time I have a say in my kids’ public education is when I vote for mayor, and to me, that’s highly undemocratic." His solution is a partially appointed and partially elected school board. "Since nobody campaigns on school issues, nobody talks about school issues," exclaimed Harsh to applause.

Whether at the dinner table or in the classroom, the challenges discussed highlighted how Cleveland families continue to face urgent gaps in support. The forum laid bare both the scale of those challenges and the diversity of visions competing to shape the city’s future — choices that will soon rest with voters as the primary election approaches.

La Villa has partnered with My Cleveland Agenda, a community listening project gathering residents’ priorities and questions ahead of the November 2025 election. In partnership with Tri-C, Signal Cleveland, and local media, we’re amplifying Clevelanders’ voices to shape a community-centered agenda. Click here to complete a short survey.

Comments